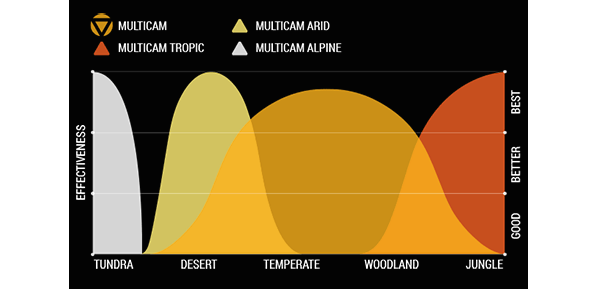

MultiCam is one of the best-known camouflage patterns of the modern era. But is it effective? In this blog post, we talk about its performance in a variety of environments.

What’s in this blog post:

Introduction

MultiCam made its debut in 2002. Since then, the pattern has enjoyed ever-increasing popularity, thanks in large part to its adoption by the U.S. armed forces.

Crye Precision invented MultiCam. In 2004, the company’s hopes for its Scorpion MultiCam pattern suffered a setback when word came down that MultiCam had lost out to UCP (Universal Camouflage Pattern) in a bid to replace the American military’s standard-issue three-colour desert and woodland patterns.

But that was not the end for MultiCam. It so happened that the expanding scope of U.S. military operations in the Middle East was such that America found itself in need of a camouflage developed specifically for use in these theatres:

Afghanistan (2001–14, “Operation Enduring Freedom”)

Iraq (2003–11, “Operation Iraqi Freedom”)

Northwest Pakistan (2004–present)

The experience of the U.S. in these hotspots offers us today insight regarding the need for a specific combination of colours so that a camouflage pattern can be considered effective in such environments.

American soldiers operating in the Middle East discovered that, within the span of a single mission, they could be confronted by landscapes of multiple earth-tones—from green trees to tan sands to bright rocks. They also discovered that this is where MultiCam excelled, for these types of terrain were the very ones MultiCam was designed to “cover”.

Image source: multicam.com

MultiCam’s fortunes rose in 2009 with the issuance of a report by the U.S. Conference Committee that found UCP highly ineffective when used in Afghanistan. This prompted the U.S. Department of Defense to quickly request a replacement pattern for UCP, one capable of providing its operatives suitable cloaking in the environments of the Middle East.

That request proved to be a turning point in the history of MultiCam.

Inducting MultiCam as OCP for Operation Enduring Freedom

Between May and November 2009, the U.S. Army—with the help of 2,000 of its soldiers—completed Phase I testing of two rival patterns. One was UCP-Delta; the other was MultiCam.

Image source: Dominic Hyde

UCP-Delta presented as a coyote-tan addition to the universal pattern. Up against it in these tests was a seven-colour MultiCam pattern. In the photograph above, you can see the two in direct comparison. Note how the coyote-tan elements blend with the grey. Also note how the macro image of the BDU becomes a shade darker with UCP-Delta, but how, on the flip side, MultiCam seems as though it would be more than adequate in arid settings.

Side-by-side comparison of UCP (left) and UCP-Delta (right).

Image source: pinterest.com

The Army initiated Phase II testing shortly after the completion of Phase I.

The second phase consisted of gathering feedback from deployed troops kitted out with one or the other of the two candidate patterns: MultiCam or UCP-Delta. The Army also conducted a photo assessment of the four other patterns (AOR II, UCP, Desert Brush, and Mirage) in a total of eight Operation Enduring Freedom zones.

The majority of soldiers participating in the testing offered feedback in which they ascribed superior performance characteristics to both MultiCam and UCP-Delta, but said MultiCam exhibited a slight edge over its rival.

This was enough to allow MultiCam to take the spotlight at the very time that there arose from the Pentagon intensified pressure for the Army to come up with an effective camouflage pattern.

In 2010, just a year after the Conference Committee’s report, MultiCam was chosen to supersede UCP. It was then given the official Army codename of “Operation Enduring Freedom Camouflage Pattern”—OEF-CP, for short.

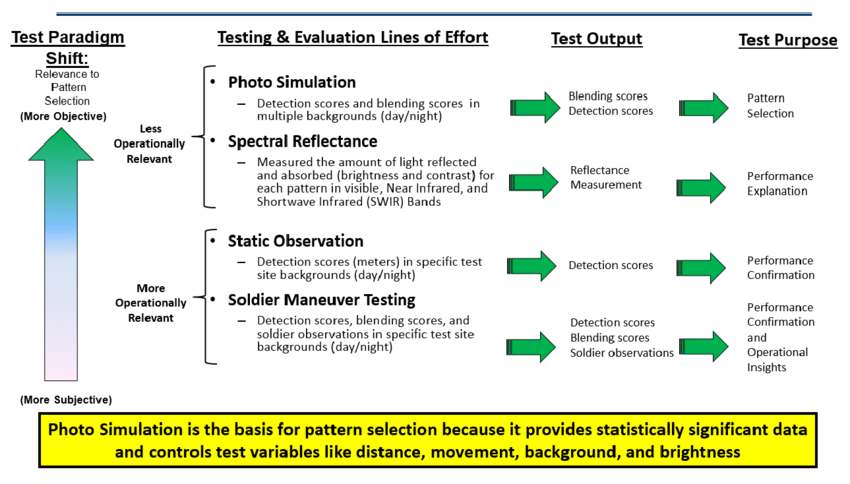

Relying on scientific data

You might by now be wondering how the effectiveness of camouflage patterns in general is determined.

Certainly the U.S. Army wondered that very thing. And the way they went about getting an answer proved to be a key factor in pushing MultiCam to the forefront of the competition for OEF-CP designation.

First, the Army decided to use a streamlined selection process built around a set of quantifiable values combined with a robust testing methodology. As it so happened, this approach produced results superior to those of previous selection processes employed by the Army. It also gave birth to greater use of analytical testing as a tool to help determine camouflage pattern effectiveness.

In a nutshell, the U.S. Army takes a two-pronged approach when it tests camouflage patterns. They are:

Detection. Specifically, the Army tests for whether the pattern can be detected at 450m by day and 250m by night.

Detection is measured by R50 value, which stands for the range where half of the subjects observe the pattern (a lower value means better concealment with the surroundings).

Blending. Here, the objective is to match the pattern with a specific background at shorter distances.

Blending is measured on a scale of 1 to 100 at two precise distances: 50m by day and 25m by night.

Image source: researchgate.net

Up until this point in the history of camouflage, there had never been so massive a collection of data sets for the purpose of evaluating the effectiveness of patterns. Making this achievement possible was the Army’s decision to utilise field-test personnel in concert with a huge sample-size of photo simulations.

Comparison of effectiveness in different environments

You’ll better understand the effectiveness of MultiCam if first we take a look at the basic structure and shape of the pattern.

The basic pattern consists of a gradient background that goes from brown to light tan overprinted with a gradient of dark green, olive green, and lime green. Atop this is a pattern-wide layer of opaque dark brown and cream-coloured shapes.

This scheme allows the overall appearance of the pattern to shift from predominantly green to predominantly brown in different sections of the fabric, while the smaller shapes break up the larger background areas. One of the tricks this plays on the eyes of an observer at a distance in a dense woodland area is it causes the small, lighter spots to be mistaken for sunlight reflections.

You can read more about different types of camouflage patterns in this blog post.

After the head-to-head OEF-CP battle ended, the Army from that time forward made it a practice to evaluate camouflage using purely quantitative parameters.

Accordingly, in 2009, the U.S. Army’s Natick Soldier Research, Development and Engineering Center gathered massive amounts of field data and published a paper in which extensive findings were presented.

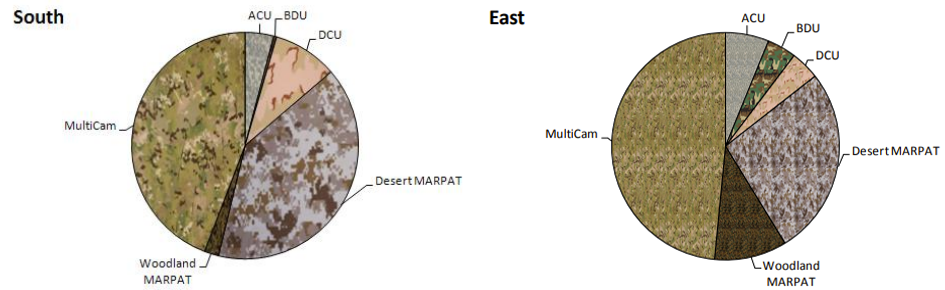

The paper examined a year’s worth of deployments in two environmentally dissimilar regions of Afghanistan. This produced results covering all seasons (see below).

Data source: U.S. Army Natick Soldier Research

The dominance of MultiCam was especially evident in Afghanistan East, receiving 47 percent of the votes. Coming in a distant second with just 26 percent of the votes was Desert MARPAT, the leading runner-up.

Desert MARPAT scored better in Afghanistan South (there, it received 39 percent of the votes) while MultiCam scored slightly lower (43 percent). Still, despite Desert MARPAT managing to close the gap, the win went to MultiCam.

The picture becomes even more interesting when you consider the Top Four reasons given by operators for preferring MultiCam over Desert MARPAT. They are listed immediately below:

|

MultiCam |

Desert MARPAT |

|

Effective in multiple environments within the region |

Has preferred colors for the region |

|

Offers good blending |

Offers good blending |

|

Has preferred colors for the region |

Offers good concealment at long range |

|

Offers good concealment at long range |

Effective in multiple environments within the region |

The strong performance of MultiCam opened the door for the pattern to enter Phase II, Part 2, of the U.S. Army’s PIP evaluation program. Ticket in hand, MultiCam would now be eligible for testing in mountainous, cropland/woodland, rocky desert, and sandy desert environments.

The Natick Lab, working in collaboration with the Aberdeen Test Center, developed a software program that allowed participants to sequentially select a computer-edited background-and-camouflage-pattern combination and then rate the blending properties of each pairing. The resulting scores (shown below) conclusively demonstrated MultiCam’s effectiveness.

|

Uniform / Equipment combination |

Rocky Desert |

Mountainous terrain |

Cropland /Woodland |

Sandy Desert |

Overall |

|

MultiCam®/Match |

93.1 |

96.0 |

72.5 |

58.3 |

80.0 |

|

MultiCam®/Coyote |

85.1 |

88.2 |

64.3 |

54.8 |

73.1 |

|

MultiCam®/Ranger Green |

83.3 |

90.7 |

70.6 |

46.7 |

72.8 |

|

Woodland Scorpion/MultiCam® |

67.7 |

88.8 |

69.2 |

58.7 |

71.1 |

|

Universal AOR/Match |

71.3 |

96.0 |

41.5 |

67.2 |

69.0 |

|

MultiCam®/Khaki |

70.9 |

87.8 |

57.8 |

55.5 |

68.0 |

|

DCU digital/Coyote |

13.6 |

31.2 |

19.4 |

19.4 |

37.6 |

|

Desert Scorpion/Khaki |

19.9 |

32.8 |

28.8 |

68.0 |

37.4 |

Data source: US Army Natick Soldier Research

More than 230 testers participated in this final stage and reviewed a grand total of 47,084 background and camouflage/equipment combinations.

MultiCam’s overall score was definite. Despite its reduced performance in a bright sandy desert environment, the pattern’s indisputable effectiveness in rocky desert, mountainous terrain, and croplands/woodlands earned it the now well-known mantle of “80 percent in most environments.”

Conclusion

The protection of American troops in combat was and is a top priority for senior leaders in the U.S. Army, Department of Defense, and Congress. As such, the DoD has over the years committed considerable resources and funding for camouflage research and development. Those investments have yielded advanced materials and innovative manufacturing processes.

At the heart of it all is the soldier’s so-called “middle-force protection layer,” better known as concealment. Indeed, the single most important contribution to the overall concealment of battlefield warriors is their combat-uniform camouflage.

Post-combat debriefings and surveys of soldiers returning home from duty in Iraq and Afghanistan reinforced military perceptions of the importance of effective camouflage. In those debriefings and surveys, most of the soldiers expressed the view that having better camouflage on their combat uniforms contributed to increased combat effectiveness.

In light of such opinions, it’s easy to understand how MultiCam became what it is today and why it has emerged as one of the most prominent, effective patterns for multi-terrain operations.

The “80-percent solution” to most terrain smartly summarises what MultiCam is. While there are now better and more specialised camouflage patterns that can outperform MultiCam in almost any setting, MultiCam’s versatility and in-theatre effectiveness remains legendary.