MOLLE is an equipment load-carrying system that is extremely recognisable and widely used. It’s key attributes are reliability, standardisation, and ease of operation. But what’s it’s origin story? This post examines how the modular MOLLE system came to be.

In this blog post:

Introduction

If we were the betting type (and we are), we’d be willing to wager that you have used MOLLE at some point in your career—or, have at least heard of it.

But on the off-chance that you are only vaguely acquainted with the MOLLE system, you’ll be forgiven for thinking of it as little more than a grid of straps to which you can attach your equipment. But those straps, forming a specific grid design, are actually a Pouch Ladder Attachment System that acts as a “connector” for the entire rig (we’ll dive deeper into that later).

As with many other things, we tend to use language loosely. That’s because language is but a tool of something larger—namely, communication. Naturally, some pieces of the tool get lost with the handing down of knowledge from one generation to the next. But the purpose of language remains, and that is to make a point and get it across to the other person.

That’s why everybody understands what you mean whether you say MOLLE webbing, MOLLE system, MOLLE channels, or any obscure combination of MOLLE and another word. Even if we’re using the name incorrectly, everybody still gets it (provided, of course, that you pronounce it properly, which, in English, is “molly").

Diving into the history of MOLLE can clear up the “misconceptions” and help you better understand what the actual word stands for.

In fact, a second bet we’d make is that you don’t know much about the story behind the invention and development of MOLLE, how it began and why. So, follow along as we explore the history of MOLLE.

A brief history of MOLLE

Carrying equipment and, specifically, doing so in an efficient manner, has been the subject of much debate as far back as the early days of the First World War. That’s understandable when you consider that soldiers were deployed for days and weeks at a time and couldn’t rely on constant resupplying. They needed to have with them water and food to survive plus their most vital equipment to stay on mission.

During the early 20th Century, this was a problem but not anything new. We can see this specific problem manifesting across the centuries. For example, in 107 B.C., a Roman general responding to the sluggishness of the logistics at the time re-envisioned the equipment his troops carried with them so as to not slow their advance. That general was Gaius Marius, whom history records as having ordered soldiers under his command to carry their own food, blankets, and extra clothing.

Fortunately, logistics have dramatically improved since then, so you’d expect that modern operators carry less. They do, but, unfortunately, the equipment itself hasn’t gotten any lighter—in fact, gear weight has actually increased since the days of the Roman Legions.

As warfare methods evolved, so did equipment requirements. In the 20th Century, soldiers carried gas masks, maps, navigation devices, radios, and more. The more equipment they required, the heavier—and bulkier—the loads. Consequently, there soon emerged a pressing need to develop a logical, high-capacity, load-bearing system.

Development of such a system kicked off in earnest during World War II. Forming its foundation were the U.S. military’s M-1945 combat pack, M-1923 cartridge belt, M-1936 pistol belt, and M-1937 BAR magazine belt. This was arguably the first well-rounded system, with patents for some of the elements dating back to the early 1900’s.

The post-World War I era should have been a time of vigorous development for load-bearing systems, but it wasn’t because many of the nations that were combatants in the “war to end all wars” spent those years digging out of economic collapse (the U.S. specifically between 1929 and 1940 was suffering through its Great Depression). It would be two decades from the end of hostilities on the Western front before an incentive to revisit the First World War’s by-then-obsolete load bearing systems materialized.

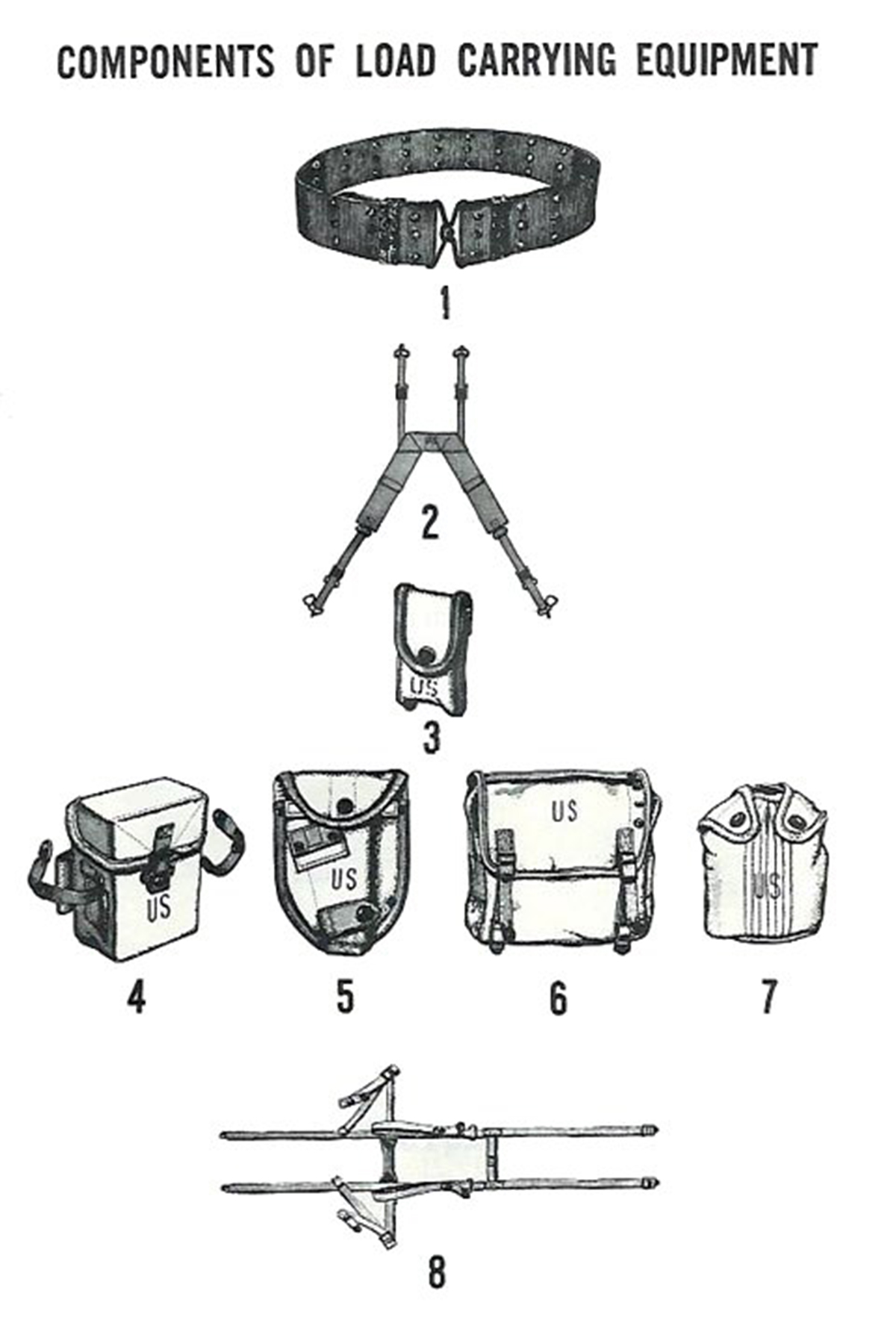

ILCE (Individual Load-Carrying Equipment)

Image source: Wikipedia

Unlike the previous iterations, ILCE came as a package. More specifically, it included the previous elements as one system:

- M-1945 combat pack

- M-1923 cartridge belt

- M-1936 pistol belt

- M-1937 BAR magazine belt

Interesting and unique was the Slide Keeper system, which was used to connect multiple pouches to the battle belt. Because of their strength and easy connectivity, this system propagated to further iterations of the load system leading up to ALICE.

MLCE (Modernized Load-Carrying Equipment)

While not a direct replacement for ILCE, MLCE was developed for tropical environments, specifically areas in Southeast Asia. The major difference between MLCE and ILCE was their material. ILCE employed then-newly available nylon, which proved to be extremely valuable for external gear. It absorbed hardly any moisture from the wet, steaming jungle—as a result, MLCE came to be seen as a lighter option than highly moisture-absorbent cotton.

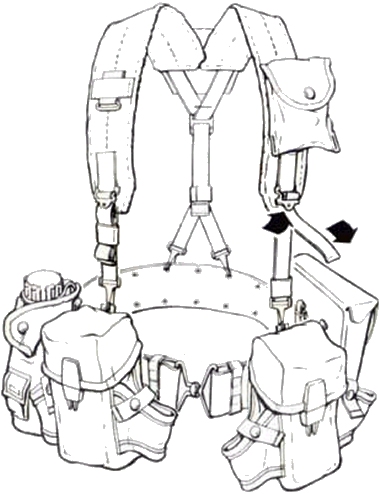

ALICE (All-Purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment)

Image source: Wikipedia

Besides MOLLE, ALICE is definitely the most known system, because of its recency, being the direct predecessor to MOLLE. It was used from 1973 to 1997 and still in use with some branches of the US Army.

The idea behind is not reinventing the wheel. Polish it and make it better. Thus a few concepts from the early load carrying systems remain intact. Combat and existential gear is still separate following the directives from 1950’s. Carry only what you need, what can be transported in other ways should be done so.

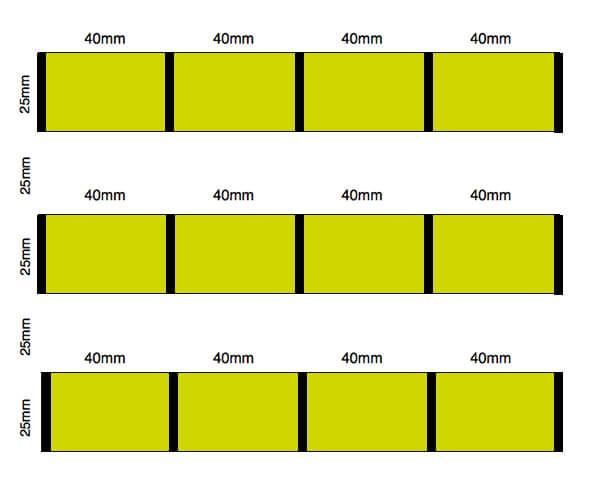

PALS - Pouch Ladder Attachment System

Without a spine, you’d be just a flopping sack of meat unable to rise up from off the ground. PALS is to MOLLE what a spine is to the human body. The brainchild of the U.S. Natick Research and Development Center, PALS was designed to remedy a problem inherent to previous systems—the lack of a standardised connector.

The tediously written patent application for PALS can give you a headache as you read it. But it does at least contain in straightforward language the basic principle of the invention: horizontal rows 25mm high by 35 mm to 40mm long, with each row spaced 25mm apart.

It’s most commonly constructed with nylon straps due to that fibre’s inherent strength and durability. Newer iterations reduce weight by incorporating the PALS system straight into the outer layer of a backpack, plate carrier, or anything else you want to connect.

The benefits of switching to a standardised connector are obvious. PALS lets you attach basically anything compatible with it—and most systems are. Using either the Natick snap, MALICE clip, or weave-and-tuck connectors, you can secure practically anything to your system.

Two other desirable attributes of PALS is high strength and ease of attaching different gear.

Notably, PALS is not the fastest connection method out there (Velcro, for instance, is much faster). However, PALS is highly reliable, works when wet, does not break if debris becomes stuck in it, and—thanks to its criss-cross webbing system—is very difficult to rip.

MOLLE (Modular Lightweight Load-Carrying Equipment)

With the experience of the earlier load-carrying systems as a foundation, development of MOLLE got underway. It’s built around six components that work together in balancing the load and enabling easy expansion/modification when needed.

The components are:

- Tactical assault panel

- Assault pack

- Medium rucksack

- Large rucksack

- Hydration bladder

- Modular pouches

Image source: Solidersystems.net

Contrary to how we use the word MOLLE today, it’s actually the name for this list of components.

MOLLE was intended to replace ALICE in 1997, but didn’t come into wide use until the early 2000s and the advent of Operation Enduring Freedom.

The system's customisability represented a significant step forward. And at the heart of it was the new PALS system (although that was not the only major change made).

ALICE came in two standard sizes; MOLLE, on the other hand, came with adjustable torso lengths and added padding on the hips and shoulders. The new system greatly enhanced comfort owing to its improved Fighting Load Carrier (which replaced suspenders and web belt) and to its lack of clips.

MOLLE allowed users to carry more weight. This was made possible by better utilisation of symmetry and positioning of the carried equipment. In the initial test, 55 kilograms (120 pounds) was deemed the “comfortable” carry weight for missions.

The final part of the MOLLE system comes from its modularity. By swapping out pouches, backpacks, and other equipment you can get a very specialised set ranging from rifleman, grenadier, pistoleer, or squad medic.

Outro

MOLLE has come a long way from the early systems designed around load management and the carrying of essential equipment. MOLLE has been with us since the beginning of this century and has since that time made inroads to the civilian market because of its reliability, ease of use, and versatility. Currently, in active use among U.S. and NATO forces, MOLLE looks as if its future as a load-management system is well cemented in the tactical space.

None of this would be possible were it not for the development of the iconic PALS system. If there’s one takeaway above all others from this blog, it’s that MOLLE and PALS cannot be considered as equivalents. MOLLE is a system of equipment designed for carrying heavy loads, while PALS is the connection method that makes it all possible.