You’ve seen it in movies or perhaps done it yourself. Parachuting. It’s a vital part of military training and serves an immense role in today’s tactical space. In this post, ex-J7 TREX NCOIC, Brigade S3 TREX NCO, First sergeant, platoon sergeant, squad leader, team leader, gunner and an ordinary Grunt talks about his experience in Airborne School and how he came to love parachuting.

In this blog post:

Introduction

Blog Post by Darko R. Roth

Hi, I am Darko, an ex-Slovenian military non commissioned officer who lived out his career in the Infantry. Currently I work as a Sales Manager at UF PRO.

My military career started in 1998 when I joined the then-mandatory six-month-long Slovenian Military Service in Vipava. I started out as reconnaissance, and it stuck with me ever since.

During the three years that followed completion of my mandatory service, I developed a really strong sense of needing to be part of something bigger than myself and doing something other than working a 9-to-5 job. I know that is sort of a cliché, but it is how I felt.

I realized that the military was the perfect channel to fulfill my help-the-team mindset. So, in 2001, I joined the Slovenian military as a Grunt in the 10th Infantry battalion.

During my 19-year military career, I completed numerous training courses. Amongst the most notable were:

- Slovenian National Airborne Training (2003)

- FIBUA, Fighting in Built-Up Areas Instructors Course (2004)

- Airborne School and IMLC Infantry, Mortar, Leader Course (2008)

- Senior NCO Career Course (2009)

- Light-Armoured Recce Leaders Course (2009)

- Complete IED Stack of Courses (2010)

- Air Assault Course (2013)

I was always a really up-front guy. Everytime I could, I would volunteer and try new things or help the team in any way I could. As luck would have it, my platoon commander was a fresh West Point graduate—which meant that he had experience with parachuting and was keen on continuing with it in Slovenia. One day, he asked if anybody would be interested in parachuting, and, of course, I was there in the front row with my hand raised and ready to jump in, literally.

In ‘03, a buddy plus the commander and I, all on our own, started off by taking up sport skydiving. We knew a guy and through him organized jumps. We spent our own money to cover the cost of equipment and plane fuel. My passion for parachuting started with the very first jump.

A parachuting course in the Slovenian army was being developed at that time. The only unit that currently trained in it was the Slovenian Military Special Force. So, seeking more and more knowledge, we continued to develop our skills and paid for it out of our own pocket until ‘08.

The platoon commander and I became good friends during this time (and remain so to this day). We started promoting the important role of parachuting in the military, offering key talking-points that included high maneuverability, quick insertions, and fighting behind enemy lines.

At this stage I was really confident in my sport skydiving skills, but there was a catch. The sport parachute itself is really different from the standard-issue T-10 military parachute. Everything was different—the descent, control, and landing. Always present in the back of my mind was an awareness that my then-current knowledge would have to be adapted.

Up until ‘08, some of my fellow buddies had already attended the Airborne School in the U.S., in combination with the Ranger course. Because it was a widely known fact that I had an affinity for parachuting, I got the notification two weeks prior to my departure for ‘0’ IMLC training that I would be staying there a bit longer.

To my surprise, I was also sent to complete the airborne course at Fort Benning, Georgia.

The airborne course

The “Gentleman's Course.” It’s called that because visiting troops from outside the U.S. get to live in a hotel and get off at 5 or 6 p.m. Monday through Friday.

The course is divided into three parts, each a week long.

Monday of the first week started and, with it, the entry physical fitness test. We needed to pass four performance tests—a 3.2-kilometer run, 42 pushups, a bunch of crunches, and a five-times full-body pull up. The bar was set really high, as I can still recall the instructors critiquing everyone’s form and explaining what they considered proper form for meeting each test’s minimum performance requirements.

I have never been a big fan of running, but the 3.2k run was easiest to pass. Other disciplines are quite “subjective.” In my case, that meant my 57 pushups satisfied the instructors’ 42.

Another thing about my airborne school experience that made a lasting impression on me was the sheer scale of it all. The 0400 formation was the perfect place to observe it. My group started off with around 500 people. There was my group and two others, so we had a total of about 1,500 people.

It wasn’t all great though. I should mention that late June in Georgia is scorching hot. Thirty-two degrees Celcius and 90 percent humidity at 0400. Just waking up and I was already sweating like a horse. Your best friend was the water canteen, which you had to carry with you at all times. The canteen holds 1 litre of water, so I think it’s descriptive enough if I say I drank 11 canteens on my first day.

Unfortunately, the instructors introduced us to a thing called “forced hydration.” This involved chugging down three canteens of water and then consuming an amount of hydration powder. The powder was intended to be mixed with the water in your canteen and then you were supposed to drink it. Nobody did it that way. Instead, we all opened the bags, emptied the powder in our mouths, and washed it down with water. Trust me when I say that the hydration powder was one of the most disgusting things I have ever eaten.

By 0600 each day, the instructors confirmed that everyone had eaten their hydration powder and we were set to start our training.

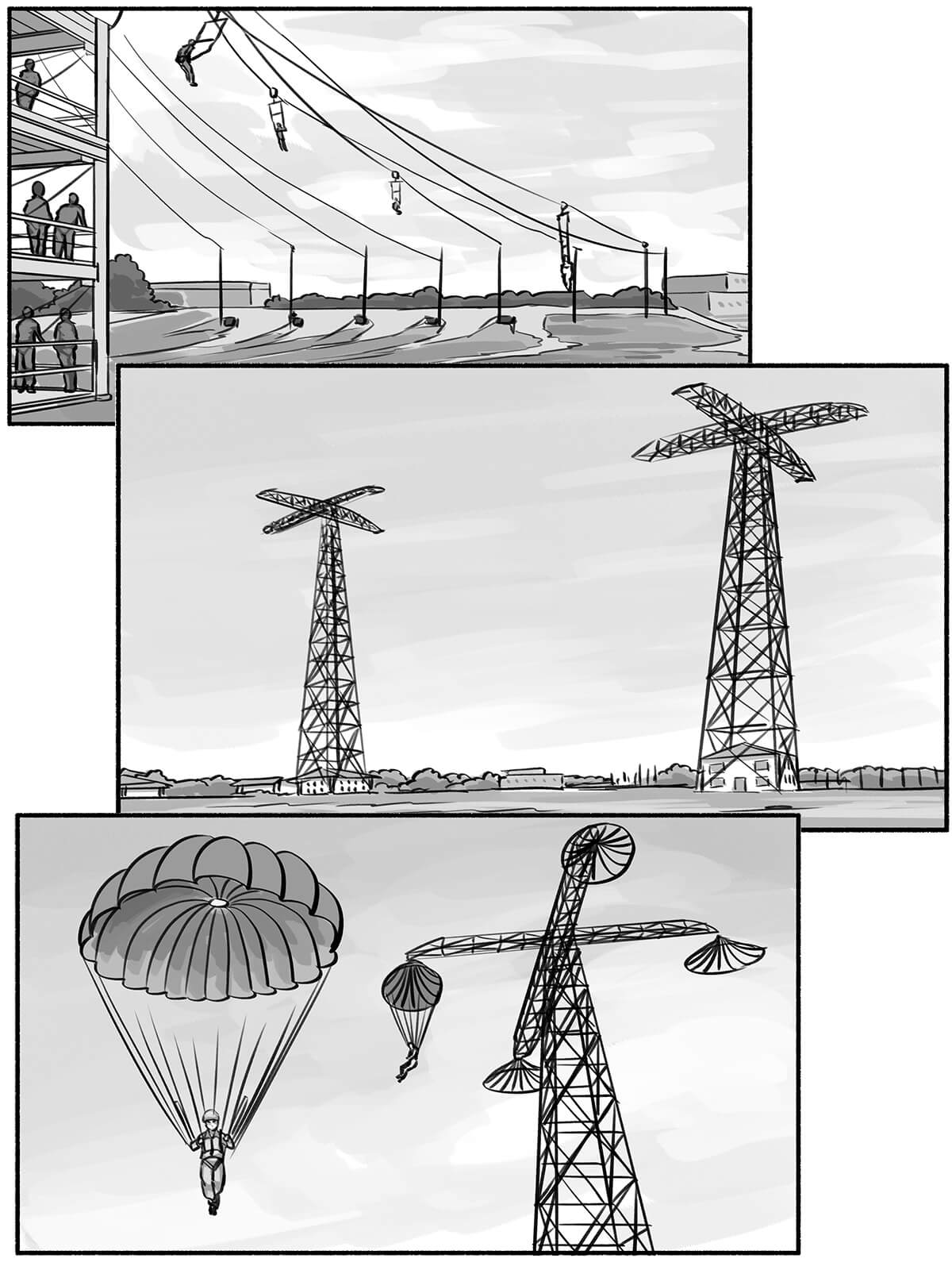

Week One was devoted to PLF—paratrooper landing fall. It’s a special way of landing to prevent injuries. Despite what the instructors say about it, the T-10 parachute carries you where it pleases. You are just along for the ride, so it is vital to have good basic skills and know how to land. The second highlight of our first week was how to properly exit the aircraft.

I also have to mention the constant mix of exercises. Running, pullups, and pushups were like bread and butter. It wasn’t something the instructors enjoyed and punished us with—it was just the name of the game called “Your Upper Body Strength.” And it’s what you have to use during your second week.

Week One focused on the exit and landing. Week Two focused on what you do in-between. This week was f***ing awesome.

There are two main drills you did. The first one is a zipline tower that teaches you how to exit, land, and properly lower your backpack and rifle. The second one is probably the synonym for parachuting—two large forked towers that simulate the actual jump. The instructor's focus is on your PLF and seeing that you execute it properly.

For the actual jump, I had to wait two whole days. Not kidding. Nothing to do with the towers or organisation (which was really good) but with the wind. You see, when you jump off, if the wind is gusting, you could end up being slammed into the tower. So not all forks were operational at the same time.

For me personally, the second tower and the actual simulated jump was harder. The wait, the lift. Monotone voice of an instructor screaming on the loudspeaker. The whole experience is really exact and polished so you are just along for the ride. Also, you have to be lucky to be selected for the tower jump—not everybody gets to jump off it.

Jump Week

The third week—a.k.a. “Jump Week”—was where things turned real and fun. The thing you signed up for finally begins and you can feel the attitude shifting to a really positive atmosphere.

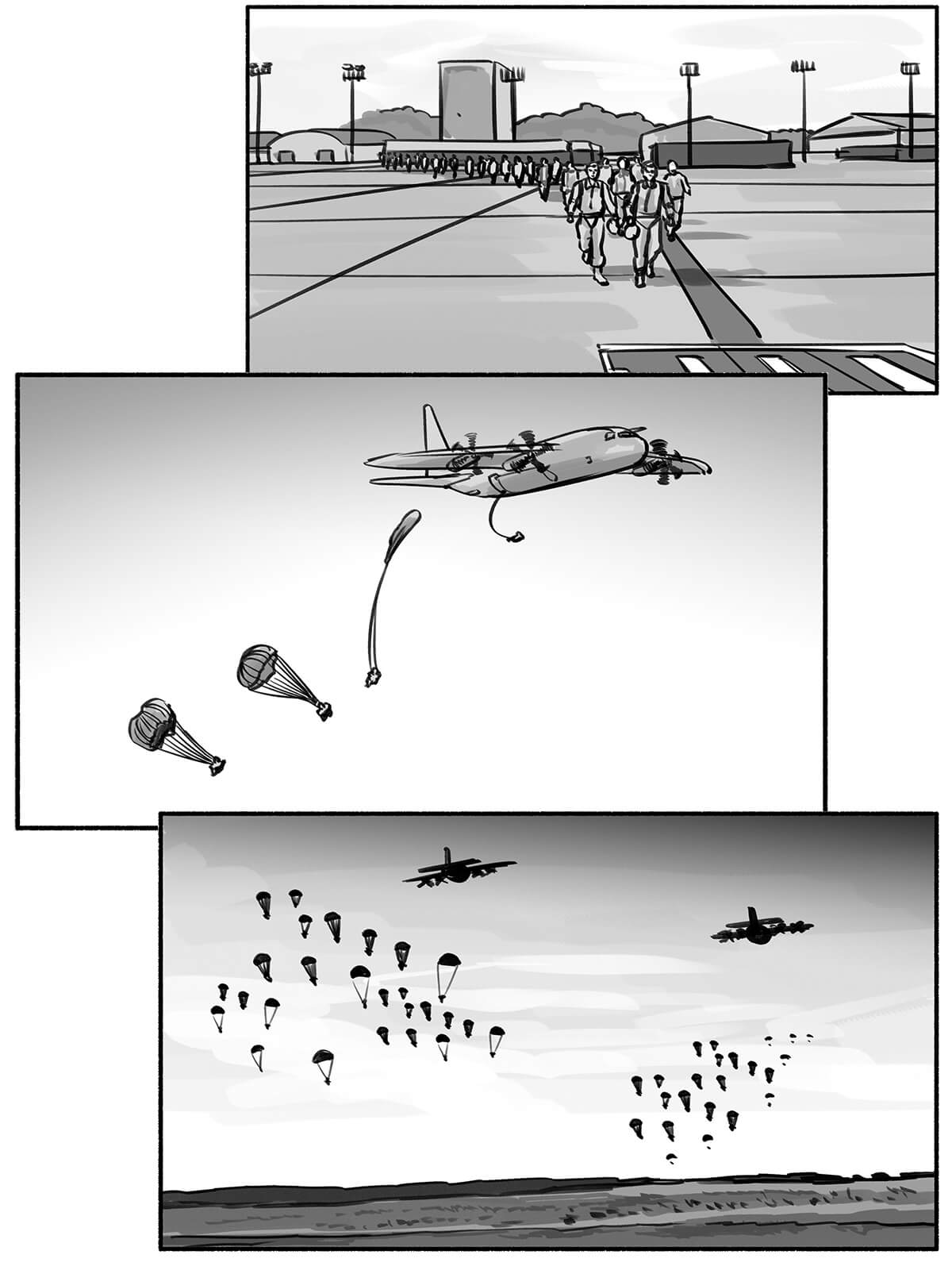

The first day started off with a light 2k jog to the airstrip. We were wearing nothing but our helmets and carrying only our water canteens. As soon as we reached the airstrip, we were sorted into three lines and received our parachutes from the riggers. The training kicks in as you put on the parachute and tighten it. Then, you are ready to go—well, almost. You have to wait until the instructors check you and confirm that you really are ready.

This whole scene was iconic. People sitting down in orderly lines, the introduction parachuting clips playing on the TVs. Not bad. But there was a catch. You weren’t allowed to take off the gear once you were confirmed good to go at the end of the JMPI (jumpmaster personnel inspection).

As an additional safety measure, it was the practice of the instructors during the JMPI to pull the straps of your chute pack really tight around your thighs. Seemingly, the instructors couldn’t be happy unless the straps were so tight that you could feel the “jewels” in your pants all the way up in your throat.

Toilet breaks were gone. No drinking water. Nothing. You had to wait around until it was your turn to jump. And it was a long wait because there were up to 1,400 people waiting to jump from just three C-130 airplanes that each held no more than 62 guys and that had to be refueled every so often. So, waiting for my first true Hollywood Jump seemed like an eternity.

My first jump was totally adrenaline pumped, despite my previous jumping. Your group gets called and you stand up, then you walk over to the waiting C-130 and board it. Everyone is dead silent in anticipation of their first jump. I can remember just the instructors talking and handing out orders.

Jumpmasters greet you as you board the C-130. They send you to your seating position. Like every piece of military hardware, the C-130 is built with exacting precision—which meant I couldn’t sit properly. My left leg was on top of the guy to my left and my right leg served as a footstool for the guy to my right. I was crammed in like a sardine. “There is always room for one more” they said.

The airplane took off and my adrenaline rush or excitement wore off. It takes about 10 minutes for the plane to climb to 300 meters and find the correct path that’ll send you straight to the drop zone. All fine and dandy.

The side doors opened. Jumpmasters started looking and titling out of the airplane. As quick as my adrenaline plummeted, it skyrocketed once the jumpmaster opened those doors.

It was all over in a flash. Two instructors started signaling the commands.

“Get ready!” I didn’t know what to do, I was barely sitting down as it was.

“Stand up!” If you could manage it, you stood up.

“Equipment check!” I inspected the guy in front of me as best I could.

“Hook up!” I clipped my static-line snap to the anchor-line cable.

“Check static lines!” I inspected my line and it seemed OK.

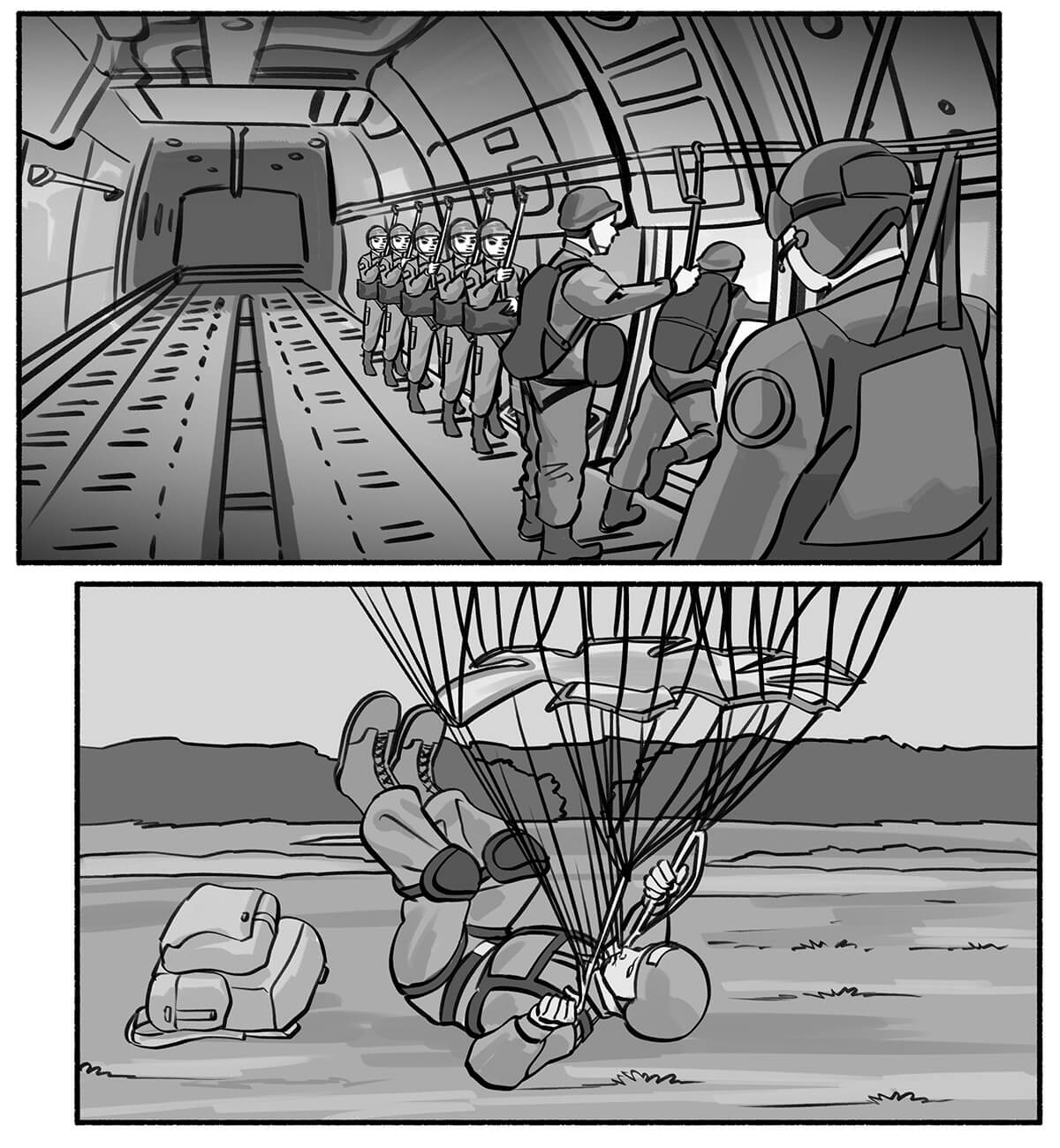

The famous shuffle to the door started. The shuffle is just a special way of walking inside the aircraft. It looks like what it sounds like, you are shuffling your way to the door.

“Go!” Didn’t know if there was even a possibility of not jumping out at this stage. I just followed the line and instantly I found myself surrounded by vast, open airspace. Deep blue sky. C-130 flying somewhere above. To me, this was one of the best feelings I ever experienced.

My parachute opened. I looked to the left and right, and saw paratroopers everywhere around me. The long wait, the uncomfortable feeling of not being able to pee or drink vanished in a split second.

The ground was fast coming toward me, preventing me from really appreciating the full glory of the earth below. Alright, I just remembered my training and the vital PLF landing technique. Of course, this went extremely successfully (if, that is, you don’t recognize sarcasm when you see it). In actuality, I smacked down straight on my arse. But totally worth it.

I stood up and packed the parachute inside the bag I was given for it. On the edge of the DZ, I saw the truck and bus that would take me back to the airstrip. There were also photographers standing by to take my picture (available for purchase afterward, of course).

Back at the base I could really feel the thrill of everybody successfully completing their first jump. Instructors allowed us to breathe it in for the day. It was pure magic.

They call it Jump Week, but it’s not actually a week—it runs only from Monday through Wednesday. However, during that short time, you get a total of five jumps.

First jump on Day Two was the combat jump. The backpack given to me was filled with blankets and I had to carry a rifle bag within which was not a gun but a wooden plank.

While we were waiting for the plane, a message blared over the intercom: one of the C-130s had mechanical problems and another had some minor issues, so both were grounded. But good news—there were a couple of C-17’s incoming to substitute for them. Hot damn.

During the JMPI, I asked to be first to jump from the airplane. Normally, you are sorted by your body weight. Heavier guys fall faster, so they usually are the first out the door. But my wish was granted, and I got to jump first.

The whole pre-jump procedure went more or less the same as my first. Until we got on the plane. Compared to the C-130, the C-17 is a luxury aircraft. Everybody had their own seat, plenty of space. On top of that, the pilot decided to do a combat takeoff. That meant a shortened sprint down the runway and a high-angled takeoff, which resulted in a momentary sense of weightlessness as the plane leveled off at altitude.

The instructors knew this was coming and it was amazing to see them sort of floating in the air. To me, this feeling was just indescribable.

Combat jump was similar to the previous. But the difference for me was significant, as I was first to jump (thanks to my loud mouth).

I got to the door and saw but one thing. Not the sky or the DZ. It was the enormous C-17 engines roaring right next to me. I started overthinking it: “Am I going to jump into them?” “Surely this has to be built safe, and I can’t get sucked into the engine, right?” and “Damn, these engines are huge…” My mind was racing. The 15 seconds I was waiting at the door was plenty of time for my mind to deviate.

“Stand at the door!”

“Go!” I got a tap on my shoulder and jumped out.

Of course, me writing this today means I did not get sucked into the engines. And the feeling on my second jump was even better, because the larger C-17 airplane meant they could carry more paratroopers aloft.

The landing was again perfect. By perfect I mean straight on my arse. Felt it a bit more because of the previous day, but Jump 2 successfully completed.

Nighttime came and with it my first Hollywood night jump. It was time to again board the C-130, which had been repaired during the day. We were greeted by two instructors standing on the boarding ramp of the plane. The intercom of the plane was set to full-blast playing “Jump Around” by Cypress Hill.

I think they found a setting where they could actually exceed the maximum volume of the intercom. You can imagine how awesome this actually was. To my sheer joy, the song was set on repeat and played the whole time, until the commands started.

This added to the night jump, itself a totally different experience. If you knew during the daytime where you were jumping, the night took that away. You could barely see the beacon situated in the DZ.

Once you exit the aircraft by night, your depth perception is really screwed. Because of the pitch black, I had no idea when I would land. I just started repeating what I had learned about “eyes on the horizon” and “keep your knees and feet together.” I really tried to anticipate the PLF. But the ground again came up too quickly and so once more I failed to make a textbook landing. Straight on my arse for the third time, despite my best efforts.

The whole experience, jumping into pitch black, the music, and everything really stuck with me. To this day, the C-130 is one of my favourite aircraft because of this.

The third day is when you have to demonstrate back to the instructors everything you learned. Day Three had two combat jumps—one during the day and one at night. Fully geared up for both.

During my fourth jump, I had the opportunity to test an emergency procedure taught during the course. As it happened, my descent occurred during quite windy conditions. This caused me to drift on top of my buddy. Because I was heavier than him it meant I was also descending faster. Both our parachutes opened, but I was straight on top of him and falling faster. Instinct and training kicked in. I started running on his parachute to avoid closing it. That trick worked and his chute remained open, but it was no walk in the park (pun intended).

On my last night jump, I had extreme good fortune. I was third in the lineup and had just exited the plane with the guy behind me when something malfunctioned on the C-130. As a result, all four of us who led the lineup landed on the edge of the DZ, but everyone else ended up landing in a forest. It was total chaos, as you could imagine.

Outro

Five successful jumps are required to complete the course and graduate. I was up for graduation that Friday.

Americans place a huge emphasis on symbolism and tradition. And it reflects most in their airborne division. The graduation ceremony—deeply imprinted in my mind—is something I’ll always be grateful for. It was memorable not only because of what it meant to the graduates but also because the division invited all local veterans and current soldiers as well as their families to attend—even a few members of the U.S. 82nd and 101st airborne divisions from World War II came to it.

The ceremony played out in front of a vintage plane. There were awe-inspiring speeches, the whole package. Packed with people and ex-graduates. It was truly an astounding scene straight out of a movie.

The award on graduation day is a pair of wings. You decide whether a family member, friend, or anybody who passed the Airborne School awards you the wings. Alternatively, one of your instructors does you the honour.

One of my buddies completed the course the week prior to this ceremony, so I asked him to award me my wings. To my luck, he was also familiar with what blood wings are and how you properly give your buddy his (although he claims this was an accident…).

Looking around me and seeing fathers and grandfathers awarding their sons and grandsons their rightfully earned wings is something that will stay with me forever—along with my wings and the experiences I lived out at Fort Benning.