A combat shirt that does what you expect it to do requires construction using an extremely functional material for the torso section. Finding such a material is no walk in the park. And when no existing material is good enough, you have to step up and create it yourself. That’s exactly what our development team did. In this post, we describe the remarkable material they created—which we’ve named Lizard/Skin—and discuss the difficulties they faced during development of this innovative fabric.

In this blog post:

Introduction

Innovation can happen in different ways. One is by taking inspiration from research you’re conducting. Another is by observing some attribute of nature that causes the tiny light bulb inside your head to turn on. Still another way innovation can happen is simply by stumbling upon something that sparks your imagination. Innovation can also come about in response to the need for a solution to a specific problem.

All four of those paths to innovation led us to the development of a new fabric: Lizard/Skin. We were looking first and foremost to solve a problem, that of producing a comfortable yet durable combat shirt offering no-melt/no-drip properties.

But how we arrived at that solution was hardly a walk in the park. In this blog, we’ll share with you the why and how of Lizard/Skin, the new lower-torso material for our Striker X Combat Shirt. And we’ll describe the challenges we faced as we traveled from idea to finished product.

The why of the Combat Shirt

Our initial problem was the combat shirt concept itself. Ironically, this concept was the solution to a previous problem we encountered—and not that long ago.

So, why was the combat shirt created in the first place? Historically, military uniforms included some sort of rugged coat or overshirt to provide basic protection against the elements and things like thorns and barbed wire. Those coats and shirts also came with large pockets for stowing vital carry-along items.

Standard military uniforms usually consisted of three components: a jacket, a pair of pants, and a shirt or t-shirt. Also, generally speaking, they were fabricated from a primary face fabric, usually either cotton, a nylon-cotton blend (NyCo), or a polyester-cotton blend (PolyCo).

In recent times, field shirts were predominantly the answer for basically everything. They were wholly compatible with backpacks and plate carriers. They had huge, readily accessible pockets. They could be worn over the pants or tucked in. They could be worn with or without a jacket. They were highly versatile. And they were well-suited to economical mass-manufacturing.

However, field shirts had one huge downside. The materials from which they were made were very thick. Consequently, it could take seemingly forever for them to dry if they became saturated with sweat or if the wearer had to wade neck-deep into the water while crossing a river or wading ashore onto a beachhead.

The idea of a combat shirt to replace the field shirt went hand-in-hand with advances being made in the development of synthetic materials. Innovators saw the combat shirt as a sportier version of the rugged field shirt. That made sense in light of the fact that soldiers frequently engaged in physical tasks requiring sometimes extreme athleticism on their part, even though they weren’t attired in functional sportswear.

Think for a moment about elite athletes and their garb. Most of them wear functional pieces beneath their jerseys and shorts. That being the case, why shouldn’t tactical gear serve a similar purpose?

Indeed, the first combat shirts emulated those functional sportswear qualities and resulted in a modified shirt design that incorporated a quick-drying, breathable, and lightweight lower-torso material. Crye Precision had this concept under development beginning in 2002 and five years later fielded it to the U.S. military. Today, Crye’s combat shirt concept is the standard for law enforcement and military uniforms.

The Comfort-Durability-FR triangle

Right, so that’s the solution then. You pack a highly breathable and moisture-wicking torso material into a combat shirt and, presto, you have your finished go-to product. Not quite. This is where the similarities between sportswear and tactical wear end.

The things a footballer has to deal with on the playing field are mild compared to those that operators must endure in the course of conducting a hot-zone mission. For example, you don’t see midfielders diving through walls of fire and intense heat. But that’s what operators do. And, because of that, operators need clothing that meets the requirements of flame retardancy and no-melt/no-drip performance. In that regard, sportswear just can’t compete.

Don’t think that’s a big deal? You couldn’t be more wrong. It totally changes the game.

With synthetic fibres it’s fairly easy to achieve good comfort and good durability (think of NyCo as an example). Synthetics permit experimentation with various fabric structures and different material percentages that fit your concept. Afterward, results that you like can be pushed further.

But, sooner or later, you’re going to run right into a brick wall.

To illustrate, take a look at these walls:

-

Example 1: NyCo. In order to get a more durable fabric, you need to increase the nylon percentage. But if you increase it too much, comfort begins to disappear, since it’s the cotton content of the blend that determines how comfortable the material feels.

-

Example 2: Denier. Increasing the denier of pure cotton jeans improves their durability. That’s because the extra thickness means more material will need to be abrasioned in order for a hole to develop. But the higher denier (which is pronounced den-year, by the way) also means the garment will weigh more and, if wet, take longer to dry out.

There are some lines we’re not able to cross with current technology, and this only gets worse when we start talking about no-melt/not-drip and flame retardancy (FR).

Let’s now take a look at the examples above through a different lens:

-

We must have a no-melt/no-drip NyCo fabric. Because no-melt/no-drip depends on having the correct cotton percentage, the percentage of nylon cannot be too high. Consequently, getting the cotton percentage correct means you can’t achieve as much durability as would otherwise be possible (as we previously discussed).

-

We need to make FR pure-cotton jeans. To keep the durability high, we increase the denier; to aquire FR properties, we need to synthetically add a coating that decreases breathability and moisture absorption (effectively erasing the very characteristics that make cotton great in the first place).

These examples illustrate the dilemma encountered in trying to solve the problem. You have a set of properties that are mutually exclusive, yet they all need to be present in order to produce a high-quality, functional garment. Increase comfort, lose durability. Increase durability, lose no-melt/no-drip. A catch-22 situation all the way around.

FR is a whole other beast to tame. For FR you need special materials (like Nomex) or technologies (like pyroshell) and do not necessarily get to pick your own fabric. To help you understand more about FR materials, read this blog post.

The Lizard/Skin solution

We needed to employ no-melt/no-drip construction. Because of that, we ended up experimenting with innumerable options for the torso material—all without success. Each material and variant we tested was prone to peeling and snagging. None was able to avoid that outcome, even when we went easy on the test materials by limiting trials to no more than 20 hours. Also, in every instance the comfort was significantly less than outstanding.

The short lifespan of the materials was primarily due to the effect of plate carriers worn by our testers. Plate carriers are a necessity for operators, but a nightmare for anyone looking to design a durable fabric. The problem is that plate carriers introduce several fabric lifespan-limiting elements that are difficult to address, such as abrasion from contact with rough edges and from Velcro fasteners in addition to the presence of a significant amount of weight. Moreover, plate carriers restrict the material’s breathability and capacity for moisture evaporation.

The brutal conditions in which combat shirts are worn take a toll on these garments as it is, but matters aren’t helped any by the fabric’s all-natural fibres—they have a fatal durability fault. They are staple fibres. That means they have a finite length, and rubbing them will inevitably expose some part of the material. As a result, those fibres are susceptible to peeling and tearing. This is normal for all natural fibres such as cotton and wool. But natural fibres are key to comfort.

A promising contender was a knitted nylon-cotton fabric. But while good with regard to comfort and durability, it suffered from significant drying issues (chiefly, it took approximately 24 hours for all traces of moisture to disappear from the wetted fibres). Another contender, Lyocell/Polyamide, had no such issues and was ultimately selected as our best pick.

What is Lyocell?

Lyocell is derived from the bark of the eucalyptus tree. What’s great about it is that moisture absorbs into the core of each fibre and thus leaves the wearer feeling better despite the material being wet. Contrast that with cotton, which absorbs moisture through the whole of its fibres. Although Lyocell is more expensive to produce, the feeling of comfort it offers wearers is excellent.

So now the torso fabric for our combat shirt solution was selected. However, we then concluded that no current option was good enough where durability was concerned. Somewhere along the line you have to reach a compromise: “Do you want more comfort or extreme durability?”

For us at least, sacrificing comfort was not possible. But as luck would have it we, happened upon a solution—ceramic dots.

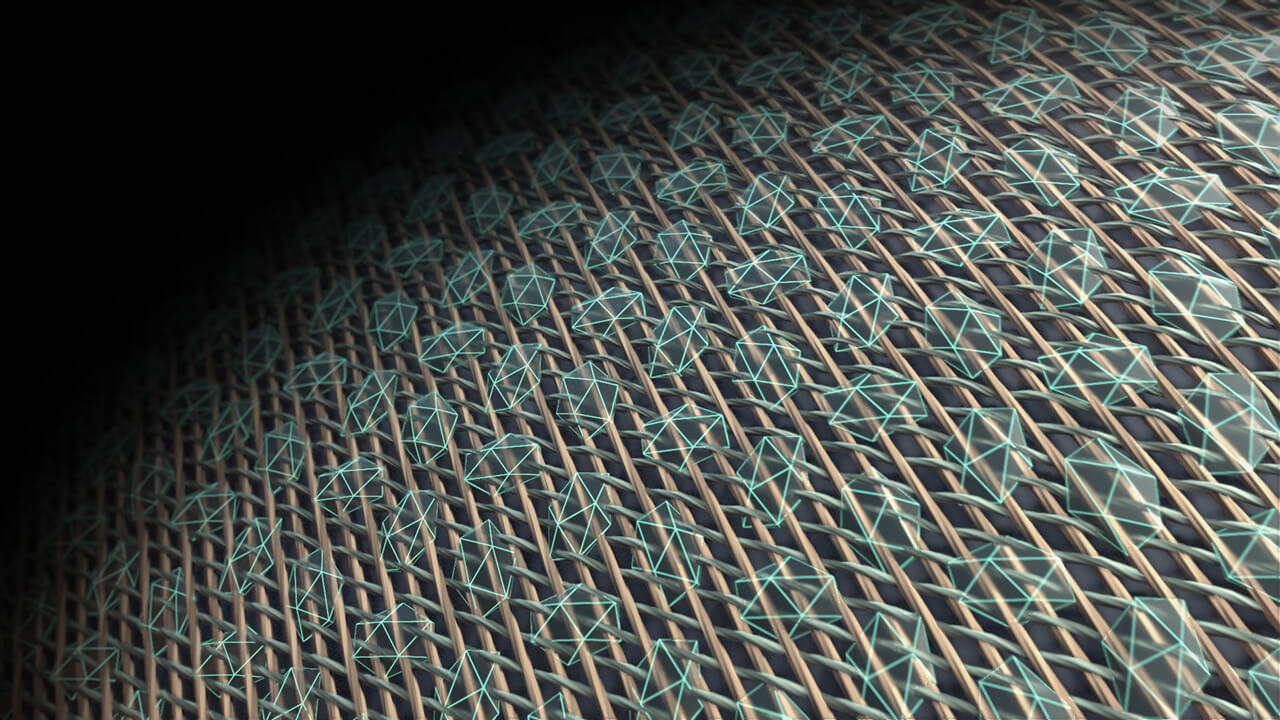

Ceramic dots are small and are glued onto the base fabric (in our case, Lyocell/Polyamide). Once affixed, they provide three-and-a-half times better abrasion resistance. This is achieved without adversely affecting other properties of the fabric—mainly breathability and moisture management.

With the addition of ceramic dots, our development team was, in our opinion, able to create one of the best possible fabrics. This material is durable enough to withstand the daily wear-and-tear that comes from toting a plate carrier and it’s comfortable enough for use in a shirt worn while performing routine duties around the base.

Outro

The search for new materials and better solutions in tactical clothing never ends. You find the best one today, but in the next couple of years it may turn out to be obsolete. This is the lifecycle of materials. We think Lizard/Skin will enjoy a very long lifecycle because it is one of the best fabrics currently available to the market.

Vous en voulez toujours plus ?