There are many possible scenarios in which it can become necessary for you on your own to clear a room. One such scenario arises from loss of comms with the rest of your team. Another scenario finds you having to return alone to a room cleared by the team moments earlier because it became apparent that some object or task detail was overlooked during the initial sweep. In this blog post we discuss lone-operator room-clearing tactics and walk you through the fundamentals of how to minimize the risk you face while “slicing the pie” without backup.

In this blog post:

Introduction

By Eliran Feildboy, founder of Project Gecko

In today's tactical space, it’s a rarity to come across an empirically valid CQB system—let alone one created with human behaviour and interaction as its guideposts.

One such rarity is the ground-breaking ITCQB system. Unlike most modern systems, ITCQB focuses on real-life scenarios and on the diverse factors found in human-to-human encounters.

You might wonder why this matters if military and LE operators are trained to never be in the position of clearing a room by themselves.

Consider this hypothetical. You and your team just finished clearing a room. Everyone else has already exited and you’re about to do likewise when your eye catches sight of a hidden door in a far corner. No one saw it while clearing the room.

Now the team is tied up clearing the next room, which means the job of clearing whatever’s behind that hidden door falls to you—and it can’t wait because, potentially, the team’s ability to secure the entire structure hinges on you sweeping solo right now.

General ‘slicing the pie’ keypoints

“Slicing the pie” is a technique for gaining information about what’s inside a room. It entails moving in a cone-shaped pattern around the apex of a room’s thresholds (usually its doors but also its windows).

At the beginning, you have zero visual information about possible threats or civilians inside. Likely all you have is audible intel gained from listening to the sounds and voices inside.

But don’t discount the intel you obtain with your ears: it may be sufficient to help you decide whether to engage or disengage.

A few pointers:

- Move your legs in the leg-pushes-leg sequence.

- Maintain the apex—eyes, firearm, leading foot-line— at all times.

- Your leading foot points toward the apex. Hips are turned toward cover.

- Stop at relevant angles (45, 90, 150,and 180 degrees).

- Look for arms or hands (typically in these situations they are extended from the body, which can make them easier to detect before a threat is able to recognise you).

- Remain stable when moving (this ensures you can bail out quickly, if necessary), do not lean into the next corner (as this exposes you to unsecured areas of the room), and plant your feet flat on the ground to keep your balance centered.

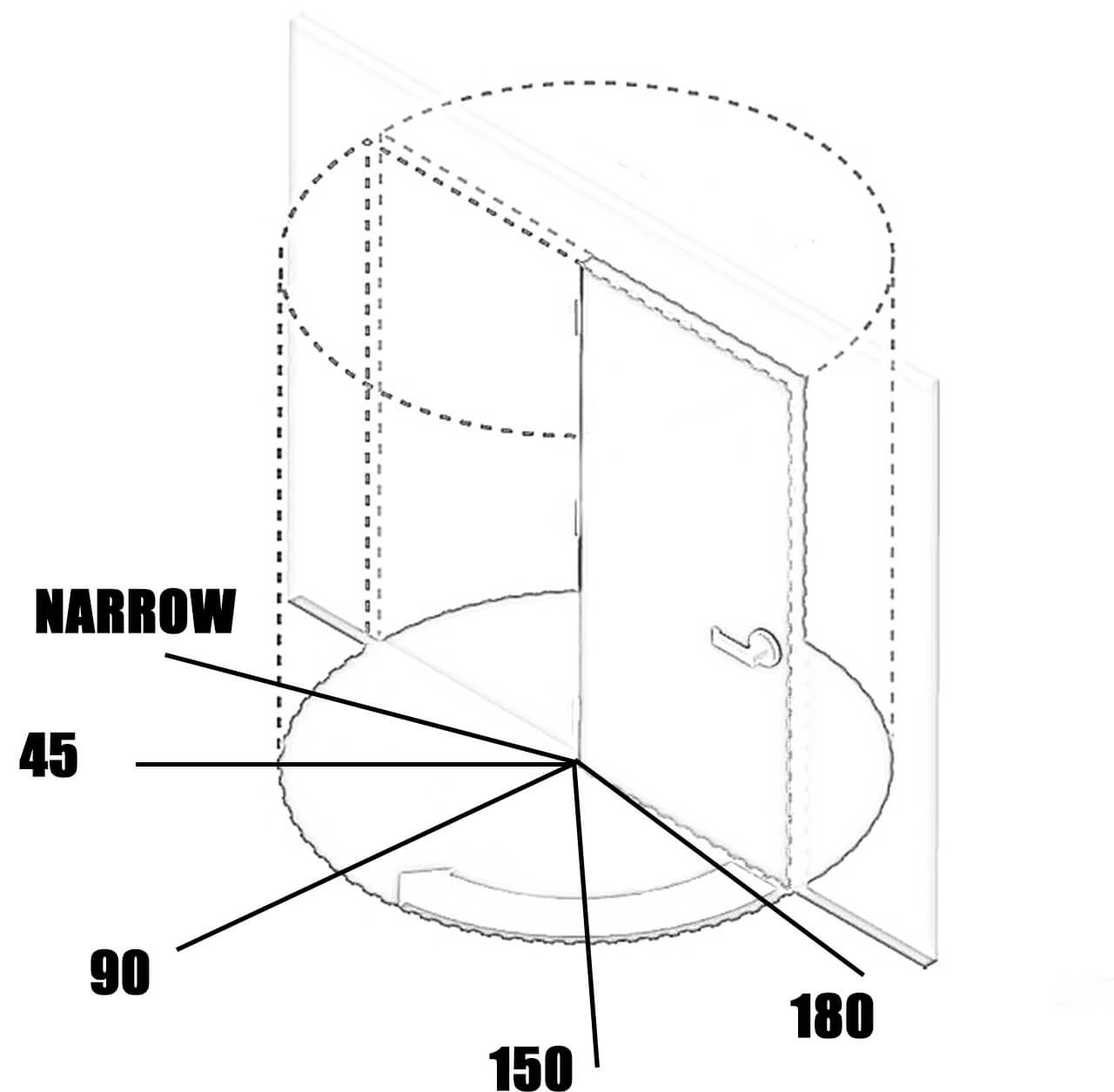

Relevance of angles when slicing the pie

Among the things you control in a room-clearing situation is the angle of entry. This angle is “measured” from the apex of the door to the last visible line into the room.

Different angles present drastically different scenarios. Each scenario affects what you can control and do to the target's mobility inside the room.

You have to fight with what you can see, not with what can see you.

The basic definition of angles in ITCQB is:

- Narrow

- 45 degrees

- 90 degrees

- 150 degrees

- 180 degrees

Narrow angle

Narrow angle

This is what you call an extremely thin exposure into the room. Typically, you encounter narrow angles first when walking alongside a wall that has a doorway built into it. You’ve entered the narrow angle when you can see the doorframe and slightly inside the room.

Although there may not be much acquirable intel awaiting in the narrow angle, there could be just enough to give you valuable insights as to what you’ll encounter in the remainder of the room.

For example, are there bloodstains on the floor? Is smoke reducing visibility? Are there voices coming from within (and, if so, how many)?

After entering the narrow angle, commence an orientation check.

Orientation check

- Stop.

- Bring your gun down.

- Breathe.

- Look behind you.

- Look back at the door.

Align your hips with the wall as soon as you enter the narrow angle and make sure your leading foot points to the door’s apex. Doing so will give you better exposure management, more cover, and enhanced body synchronisation of the door threshold. Most importantly, it will facilitate increased mobility because positioning your body with hips toward the wall allows you to stay fluid so you can move around the narrow angle better and bail out quickly if the situation requires it.

Progression to 45 degrees

Progression to 45 degrees

The next relevant angle is 45 degrees. This is your point of contact with the flank of the room even as you’re concealed by the room. You’re still gathering intel about the room—let's say different compartments, multiple doorways, or multiple targets.

Keep your gun down while slicing. This minimizes your exposure to the inside of the room and prevents triggering toe room.

Snapping to 90 degrees

Snapping to 90 degrees

This angle allows you to see the center of the room where people will most likely stand if we’re not engaging with them.

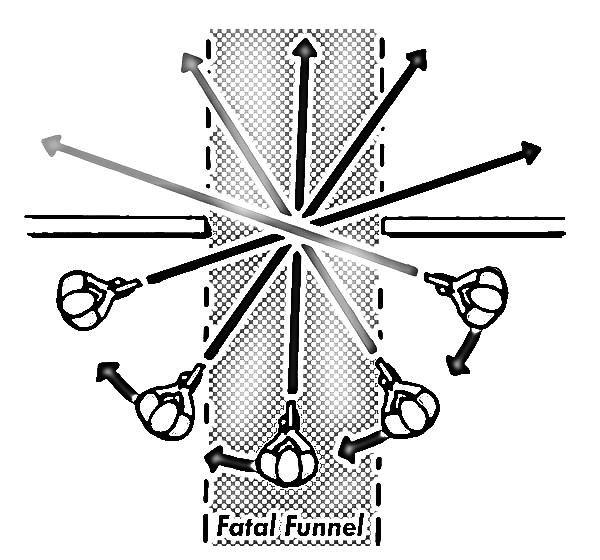

You may be acquainted with the term “fatal funnel” and have heard it used to denote the area between 45 and 135 degrees. But what exactly is a fatal funnel? It’s a term for areas where you are easily seen but cannot easily engage/disengage targets inside the room.

Despite the dangers inherent to the fatal funnel, the 90 degree angle can be a valuable asset in that it allows you to divide the room into two sections—one, the controlled area; the other, the uncontrolled area.

Image source: artofmanliness.com

However, the 90 degrees angle is trickier than the others. Even having your firearm turned down slightly still allows the target to see its muzzle before you enter. Exposure risk is worst when your angle is between 60 and 90 degrees.

A recommended solution is to snap as soon as you start to isolate to 90 degrees. Do this in a single step. It can leave a target who has seen your muzzle significantly less time to react. It can also prevent triggering the room.

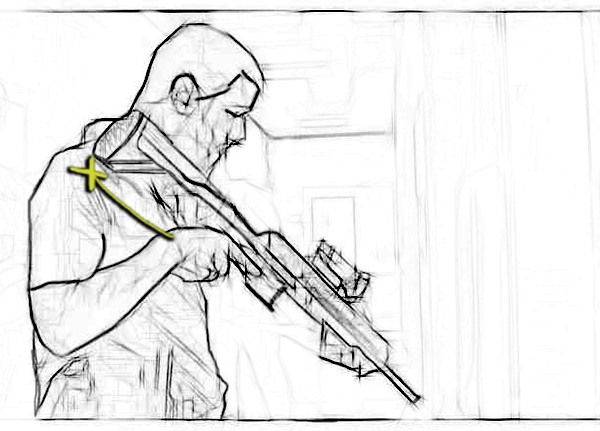

150 Degrees

150 Degrees

In traditional CQB, angles beyond 90 degrees aren’t identified. They’re used in the ITCQB system to highlight the increasing danger of progressively opening the room.

From 90 to 150 degrees, you can reduce the possibility of exposure by compressing the weapon when closing in. Compressing is accomplished by bringing the stock up higher on your shoulder while keeping the barrel pointed down.

Compressing does not impede your reaction time. You’ll still be quick in presenting your weapon and, by keeping the line-eyes/weapon/leading-foot positioning, you won’t find it necessary to use the sight.

180 Degrees

180 Degrees

This is called the “hard corner.” Here, your goal is to cheat the angle and see as much of the room as you can.

As the final part of the angle approaches, you attack the corner—meaning you quickly step inside with your leading foot (flat and stable so you can bail out if needed) and align your weapon.

One final step: after securing the final angle, look back over your shoulder to make sure no threats are present and able to attack from behind.

Outro

Focusing on five key angles as the golden rule allows you to methodically and consistently clear rooms with high emphasis on minimizing your exposure and thus safety.

Strong fundamentals when slicing the pie are a necessity in both solo and team clearing a room. Once you understand angles and their relevance you can better understand what situation you can use for clearing stoppages, bailing out and proactivity.

In the ITCQB system you don’t rely on theory but actual datasets from real life scenarios.